MARRIAGE

Marriage (àvàhana) is the formal and legal joining of a man and a woman which usually takes place in a ceremony called a wedding. From the Buddhist perspective marriage is a secular institution, an arrangement between two people or two families and the Buddha did not insist upon monogamy, polygamy, polyandry or any other form of marriage. Brahmanism recognized eight forms of marriage, the most common being those arranged by the parents or guardians and which usually included a payment. Less common but still recognized were where the couple chose each other with the parents approval (âsura), or where the couple married without their parent's permission (Gàndharvah). This last type usually involved elopement. Abduction (Ràkùasa) was allowed for the warrior caste and sometimes resulted in violence. The Vajjians used to `abduct others' wives and daughters and compel them to live with them', a custom the Buddha considered socially detrimental (D.II,74). A type of marriage mentioned in the Jàtakas was called Svaya§ara wherein usually a girl but sometimes a boy chose a partner from a number of suitors. Such ceremonies would usually take place at a public gathering.

The Tipiñaka mentions the Buddha's wife and his son Ràhula so we know he was married, but it provides no information about what kind of marriage he had or his wedding ceremony. However, later fictional biographies of the Buddha usually portray him as having a Svaya§ara marriage which suggests that this was the type of marriage that early Buddhists thought of as the ideal.

According to Brahmanical law a girl had to be married of within months of her first menstruation, after which her father would incur more blame the longer he delayed the marriage. The early Buddhists considered 16 to be a suitable marriageable age (patta soëasa vassa kàle, pattavaya, Ja.I,421). It was thought good for couple to be the same age (tulyavaya), although the Kàma Såtra (4th cent CE) recommends that the bride be three years younger than the groom. The Buddha thought it inappropriate and foolish for old men to marry women much younger than themselves (Sn.110).

Although the Buddha did not advocate any particular form of marriage, we can assume that he favoured monogamy. His father Suddhodana had two wives and as a prince he could have had several wives also, but he chose to have only one. In a discourse on marriage, the Buddha only discusses monogamy, again implying that he accepted this as the best form of marriage (A.IV,91-3). He said that if a woman lacks merit she might have to contend with a co-wife (sapattã, S.IV,249) and the Tipiñaka discusses the disadvantages of polygamy for women. `Being a co-wife is painful' (Thi.216), `A woman's worst misery is to quarrel with her co-wives' (Ja.IV,316). Such problems are confirmed by the Kàma Såtra which describes the tensions and manoeuvrings between several wives in the same household. There seems little doubt that it was for these reasons that the Jàtaka counseled: `Do not have a wife in common with other'(Ja.VI,286).

Having been both a husband and a father, the Buddha was able to speak of marriage and parenthood from personal experience. A husband, he said, should honour and respect his wife, never disparage her, be faithful to her, give her authority and provide for her financially. A wife should do her work properly, manage the servants, be faithful to her husband, protect the family income and be skilled and diligent (D.III,190). He said that a couple who are following the Dhamma will `speak loving words to each other' (a¤¤ama¤¤a piyaüvàdà, A.II,59) and that `to cherish one's children and spouse is the greatest blessing' (puttadàrassa saïgaho etaü maïgalam uttamaü, Sn.262). He said that `a good wife is the best companion' (bharyà va paramà sakhà, S.I,37), and the Jàtaka comments that a husband and wife should live `with joyful minds, of one heart and in harmony' (pamodamànà ekacittà samaggavàsaü, Ja.II,122). The Buddha criticized the brahmins for buying their wives rather than `coming together in harmony and out of mutual affection' (sampiyena pi saüvàsaü samaggatthàya sampavattenti, A.III,222), implying that he thought this a far better motive for marriage. `In this world, union without love is suffering' says the Jàtaka (lokismiü hi appiyasampayogo va dukkha, Ja.II,205).

Having been both a husband and a father, the Buddha was able to speak of marriage and parenthood from personal experience. A husband, he said, should honour and respect his wife, never disparage her, be faithful to her, give her authority and provide for her financially. A wife should do her work properly, manage the servants, be faithful to her husband, protect the family income and be skilled and diligent (D.III,190). He said that a couple who are following the Dhamma will `speak loving words to each other' (a¤¤ama¤¤a piyaüvàdà, A.II,59) and that `to cherish one's children and spouse is the greatest blessing' (puttadàrassa saïgaho etaü maïgalam uttamaü, Sn.262). He said that `a good wife is the best companion' (bharyà va paramà sakhà, S.I,37), and the Jàtaka comments that a husband and wife should live `with joyful minds, of one heart and in harmony' (pamodamànà ekacittà samaggavàsaü, Ja.II,122). The Buddha criticized the brahmins for buying their wives rather than `coming together in harmony and out of mutual affection' (sampiyena pi saüvàsaü samaggatthàya sampavattenti, A.III,222), implying that he thought this a far better motive for marriage. `In this world, union without love is suffering' says the Jàtaka (lokismiü hi appiyasampayogo va dukkha, Ja.II,205).

According to the Buddha's understanding, if a husband and wife love each other deeply and have similar kamma, they may be able to renew their relationship in the next life (A.II,61-2). He also said that the strong affinity two people feel towards each other might be explained by them having had a strong love in a previous life. `By living together in the past and by affection in the present, love is born as surely as a lotus is born in water' (Ja.II,235). This idea is elaborated in the Mahàvastu: `When love enters the mind and the heart is joyful, the intelligent man can say certainty, ßThis woman has lived with me beforeû.'(Mvu.III,185).

The ideal Buddhist couple would be Nakulapità and Nakulamàtà who were devoted disciples of the Buddha and who had been happily married for many years. Once Nakulapità told the Buddha in the presence of his wife: `Lord, ever since Nakulamàtà was brought to my home when I was a mere boy and she a mere girl, I have never been unfaithful to her, not even in thought, let alone in body'(A.II,61). On another occasion, Nakulamàtà devotedly nursed her husband through a long illness, encouraging and reassuring him all the while. When the Buddha came to know of this, he said to Nakulapità: `You have benefitted, good sir, you have greatly benefitted, in having Nakulamàtà full of compassion for you, full of love, as your mentor and teacher' (anukampikà, atthakàmà, ovàdikà, anusasikà, A.III,295-8). From the Buddhist perspective, these qualities would be the recipe for an enduring and enriching relationship Ý faithfulness, mutual love and compassion and being each others' spiritual mentor and teacher.

The ideal Buddhist couple would be Nakulapità and Nakulamàtà who were devoted disciples of the Buddha and who had been happily married for many years. Once Nakulapità told the Buddha in the presence of his wife: `Lord, ever since Nakulamàtà was brought to my home when I was a mere boy and she a mere girl, I have never been unfaithful to her, not even in thought, let alone in body'(A.II,61). On another occasion, Nakulamàtà devotedly nursed her husband through a long illness, encouraging and reassuring him all the while. When the Buddha came to know of this, he said to Nakulapità: `You have benefitted, good sir, you have greatly benefitted, in having Nakulamàtà full of compassion for you, full of love, as your mentor and teacher' (anukampikà, atthakàmà, ovàdikà, anusasikà, A.III,295-8). From the Buddhist perspective, these qualities would be the recipe for an enduring and enriching relationship Ý faithfulness, mutual love and compassion and being each others' spiritual mentor and teacher.

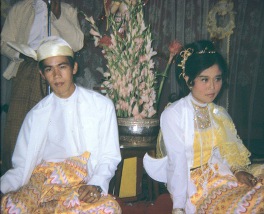

It seems that throughout history most ordinary Buddhists have been monogamous, although kings were sometimes polygamous and fraternal polyandry was common in Tibet until just recently. In the highlands of Sri Lanka during the medieval period polyandry was practised, and it still is in parts of Ladakh and Spiti. Today, monogamy is the only legally accepted form of marriage in all Buddhist countries. There is no specific Buddhist wedding ceremony; different countries have their own customs which monks usually do not perform or participate in. However, just before or after the wedding the bride and groom often go to a monastery to receive a blessing from a monk. See Celibacy, Divorce and Yasodharà.