LIFE, THE STAGES OF

For centuries philosophers and moralists have tried to identify the stages a human being will or should pass through on their journey from birth to death. In Western thought the most famous of these is probably Shakespeare's Seven Stages of Man. In conventional thinking in ancient India, life was said to have three stages; youth (pañhamavaya), middle age (majjhimavaya) and old age (pacchimavaya, Ja.I,79). Hinduism gradually evolved the idea that the proper course of a person's life (à÷rama) is to be a student, a householder, a retiree and finally a religious ascetic.

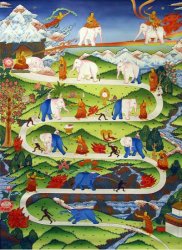

Buddhist thinkers too gave thought to this subject. The Visuddhimagga identifies ten stages each of ten years duration that mark a person's life. `Concerning these decades, the first for a person who lives to be a hundred is called the tender decade, because one is a tender, unsteady babe then. The second is called the sport decade, because one is fond of games then. The third is called the beauty decade because a person's beauty reaches full bloom during this period. The fourth decade is called the strength decade because a person's strength is at its peak then. The next ten years are called the understanding decade because one's understanding is stable, and even one who is not smart has got at least some understanding by then. The next ten years are called the decade of decline because one's fondness for games, one's beauty, strength and understanding begin to wane. The next ten years are called the stooping decade because the posture begins to stoop. The next ten are called the bent decade because a person's posture becomes bent like a plough. The penultimate ten years are called the decade of dotage because one is in one's second childhood and becomes forgetful. The last decade is called the prone decade because those who manage to reach a hundred spend most of their time lying down'(Vism.619).

The Buddha gave his own version of the stages of life, although as with so much else, he took an entirely different perspective from most other thinkers on the subject. He spoke of four stages in a person's life. The first is that of the `tender baby, vulnerable, lying on its back and playing with his own faeces'. He identified this as the individual's initial pleasurable experience, albeit a crude one which would eventually be grown out of. In the next stage `that child grows older and with the awakening of his sense faculties plays with toy ploughs, tip-cat, jumping, leaf windmills, marbles, toy chariots and toy bows'. Such pleasurable games are, the Buddha said, at a higher level but will nonetheless eventually be outgrown also. At the third stage `having grown older, with the complete development of the sense faculties and experiencing the five sense pleasures, he comes under the sway of, gripped by, fascinated with and addicted to, objects seen with the eye, sounds heard with the ear, odours smelled with the nose, tastes tasted with the tongue and sensations felt with the body'. In the last stage the individual gives up sensual pursuits, embarks on the spiritual quest and attain peace and joy through meditation (A.V,204-9). This, the Buddha said, is `the lifestyle more exalted and more refined than the former ones'(abhikkantataro capaõãñataroco, A.V,209).

The Buddha's vision of the stages of life differs considerably from those of other thinkers. Most emphasise the physical factor (i.e. the maturing and decaying of the body), whereas the Buddha focuses entirely on the psychological. Most others see the various stages as natural, inevitable, inescapable even. In the Buddha's schema only the first three stages could be said to be natural. We can, he taught, create a more fulfilling destiny for ourselves by choosing to break away from the pull of sensory stimulation and develop the mind to its highest potential. Most other versions of the stages of life end in death while the Buddha's ends in the attaining of a state of clarity, peace and joy in which death is seen as inconsequential.