BLIND MEN AND THE ELEPHANT, THE PARABLE OF THE

The parable of the blind men and the elephant is probably the most widely known and the most loved of all the world's parables. By far the earliest version of this parable is to be found in the Udàna, and is attributed to the Buddha (Ud.67-9). The parable's appeal is due to how well it makes its point, its striking juxtaposing of man and beast and its gentle humor. The background to the Buddha telling this parable is thus. Some monks in Sàvatthi noticed a group of non-Buddhist monks quarrelling with each other about some philosophical or theological issue. Later, they mentioned what they had seen to the Buddha and he said, `Wanderers of other sects are blind and unseeing. They don't know the good and the bad and they don't know the true and the false. Consequently they are always quarrelling, arguing and fighting, wounding each other with the weapon of the tongue.' Then the Buddha related his famous parable.

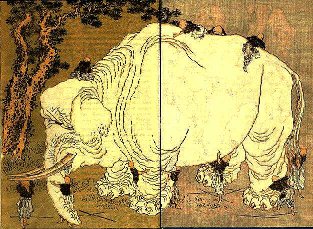

`Once here in Savatthi, the king called a certain man and said: ßAssemble together in one place all the men in Sàvatthi who were born blind.û Having done as the king commanded, the king then said to the man, ßNow show the blind men an elephant.û Again the man did as the king commanded, saying to each as he did, ßOh blind man, this is an elephant and this is its head. This is its ear. This is its tusk. This is its trunk. This is its body. This is its leg. This is its back. This is its tail. This is the end of its tail.û This having been done the king addresses the blind men saying, ßHave you seen an elephant?û and they replied, ßWe have sire.û ßAnd what is an elephant like?û he asked. And the one who had touched the head said, ßAn elephant is like a potû while the one who had touched the ear said, ßAn elephant is like a winnowing basket.û The one who had touched the tusk said, ßAn elephant is like a plough poleû while the one who had touched the trunk said, ßIt is like a plough.û The one who had touched the body said, ßIt is like a granaryû and the one who had touched the leg said, ßIt is like a pillar.û The one who had touched the back said, ßIt is like a mortarû, the one who had touched the tail said, ßIt is like a pestleû while the one who had touched the end of the tail said, ßAn elephant is like a broom.û Then they began to quarrel saying, ßYes it is!û, ßNo it isn't!û, ßAn elephant is like this!û, ßAn elephant is like that!û until eventually they began fighting with each other.' Having told this story, the Buddha summed up its meaning in a terse little verse Ý `Some monks and priests are attached to their views and having seized hold of them they wrangle, like those who see only one side of a thing.'

The key to understanding the meaning of the parable is in the last line of this verse; seeing only one side of a thing (ekaüga dassino). This is but one example of where the Buddha gives advice about how to form a more complete, a more accurate view of reality. Here he is suggesting one important point Ý that we should not mistake the part for the whole. In other places he advises keeping personal biases out of the way when assessing views, taking time to form opinions and even when having done so, keeping an open mind so as to be able to consider other points of view.

After the Udàna, the earliest mention of the parable of the blind men and the elephant is to be found in the Syadvadamanjari, a Jain work where it is used to illustrate the Jain doctrine of relativity of truth (anekantavàda), the idea that `every view is true from some standpoint (naya) or other and in general no view can be categorically false.' After this the parable spread throughout India and beyond. It appears in Brahmanical and Hindu works, in some Persian collections of stories and even in one of the works of the Turkish Sufi mystic Rumi. Today there are numerous children's books about it or which include it.